“Your decision-making

behavior

in uncertain and

hazardous situations,

differs significantly

from your routines,

everyday decisions.”

In the heart of Norway’s North Sea oil operations, a fascinating insight emerged—not from deep under the seabed, but from deep within an organisation.

The year had been a success. One of Norway’s major oil companies had delivered strong annual results. Exploratory drilling yielded promising new finds, and innovative technologies were transforming oil production.

The atmosphere was electric. Optimism filled the hallways. Leadership decided to celebrate this momentum with something tangible: a bonus pool to reward innovation and bold decision-making.

As part of the leadership development team, I was brought in to support the HR department in distributing these rewards. Simple enough, right? – Not quite.

We asked managers across the company to nominate individuals who had demonstrated outstanding decision-making. What came back was… unexpected. Most of the nominees were mirror images of the managers who nominated them.

Without realizing it, leaders were nominating people who thought, acted, and behaved like themselves. In other words, they were using themselves as the gold standard. The risk? A self-reinforcing cycle of sameness—a culture of clones.

We knew this wouldn’t fly. People would notice. The so-called “face factor” (as we nicknamed it) would spark backlash, and rightly so. We needed a better, more objective framework—something that reflected the true complexity of decision-making across the organization.

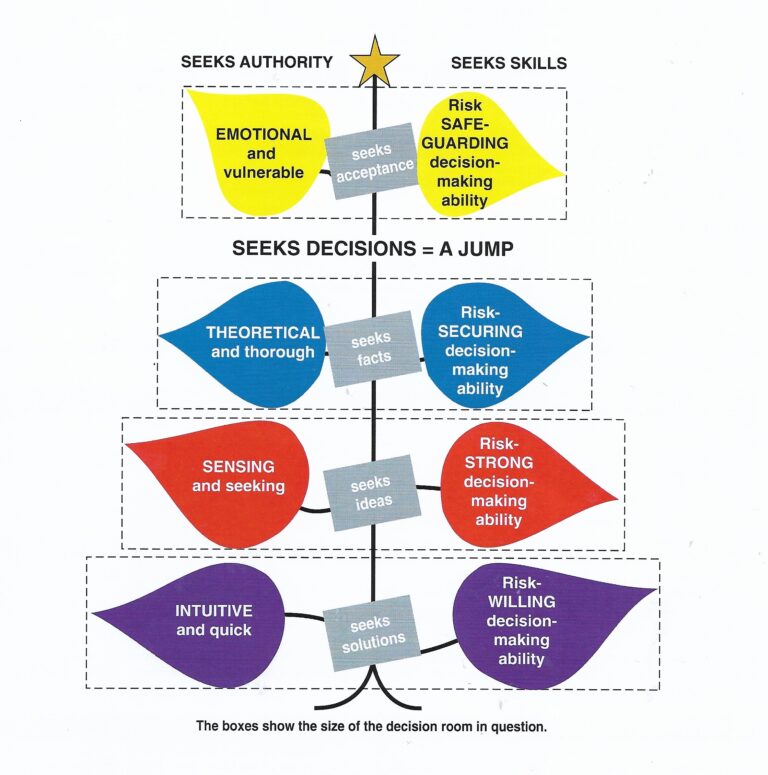

That’s when the Decision Tree was born.

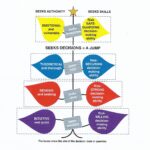

Instead of rewarding a particular type of person, we introduced a tool that celebrated the range of decision styles used in a high-stakes industry. The Decision Tree became our new compass.

Inspired by communication models we had used in earlier SGL leadership programs, the Decision Tree was built on four distinct levels of decision-making—each represented by a branch and coloured leaves. Each “branch” reflected a different kind of contribution, grounded in the real-life complexity of personalities.

At its core were two dominant profiles:

Both were vital, especially when appointing leaders for new projects. One wasn’t better than the other—they were complementary. The Decision Tree gave us a shared language and an inclusive standard, far removed from any “gold” class.

The nominations became more thoughtful. The conversations became deeper. And best of all, the awards By shifting the focus from similarity to situational strength, we changed the game. Leaders started seeing value in diversity—not just in background or identity, but in decision-making approach, felt truly earned.

To confirm our identified Decision Profile, we used the answers from Decision Color and Decisions Partner. – These combined to produce one of four possible outcomes: No/Yes – No/No – Yes/Yes – Yes/No – In the following, we’ll describe what each of these meant—both for the individuals themselves and for their leadership style.

What’s truly exciting was however: What started as a bonus initiative ended up reshaping how we thought about leadership potential.